Fayetteville VA Medical Center hosted its health fair at Goldsboro Community-Based Outpatient Clinic on April 10. Department of Veterans Affairs Photo

This is the fifth of a series of posts looking at how to impact the veteran suicide epidemic using a public health approach. You can see the original overview post here.

Several years ago, a veteran walked into their local Vet Center the Friday after Christmas. They’d been out of the military for a couple of years, and things weren’t going too bad, but things weren’t all that great either. Even though it was a holiday weekend, the veteran was seen by someone that day; pretty cool. They filled out a bunch of paperwork, had a good conversation. The screening clinician told the veteran that someone would be in contact with them to set up an appointment. It may take a bit, because of holiday staffing, but the group of them would talk and they would be assigned a clinician.

A week went by. No big deal, it was the holidays, understandable. Now it’s the first week in January. Still haven’t heard anything; well, send them an email at the end of the week. By the middle of the next week…now the second week in January…the veteran gets an email back saying that they have been assigned a clinician, and that the veteran should hear from them soon. The new therapist contacts the veteran at the beginning of the following week and scheduled for the next available appointment.

For the first week in February.

Forty-five days after the veteran voluntarily walked into the Vet Center, they have their first actual therapy appointment. A matter of timing? Of staffing? There could be a lot of things that this story illustrates, but at it’s core it shows the difficulty for a veteran to access mental health care when they’re ready for it. This isn’t to bash the VA…community providers have the same challenges when it comes to availability of therapists. Some VA mental health clinics, both at the main VA and the Vet Centers, have much better response times than this, and some have worse. The same goes with community providers.

Access to Care is Critical to Reducing Veteran Suicide

My aim is not to point fingers, but to illustrate a problem; there is a lack of access to responsive treatment for veterans seeking support for mental health concerns. While the first three suicide prevention strategies highlighted in this series increase protective factors around suicide…improve connectedness, increase economic stability, and promote education and awareness…this intervention strategy focuses on reducing risk factors for suicide. The Centers for Disease Control’s Technical Package identifies access to effective mental health care as a critical component of programs that have been shown to reduce suicide in the veteran population. In a study conducted in 2014 looking at health contacts in the year before death by suicide, effective mental health systems that have proven to reduce suicide have improved access to care as a component.

So what does improved access to effective mental health care look like for veterans? It means reducing the shortage of mental health care providers in our communities. Improved access to care is helping veterans get the care they need, when they want it, by someone who understands the unique characteristics of military service and lifestyle. It also means VA and community providers working together to provide care to all who served, including those not eligible for VA services.

Reduce Provider Shortage

A critical aspect of improving access to mental health care for veterans is increasing the number of mental health providers in the community. The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) has designated health professional shortage areas (HPSAs) throughout the country in three categories: primary care, dental, and mental health. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation has collected HPSA data for the country as a whole, and individual states. In order to address the shortage of mental health professionals in the United States…meaning increasing the number of mental health professionals relative to the population with consideration of high need…there would need to be over 6,000 more clinicians nationwide. And this is considering one mental health professional per 30,000 people…20,000 if the area is considered a high-need community.

So what can be done about it? Someone reading this might say, “okay, I may be able to help with education and housing and connectedness, but what can I do about reducing mental health provider shortage?” Communities together can address shortages through policy and legislation. Incentives and tax breaks for mental health providers working in underserved locations. And this is just to address the shortage of mental health professionals at large.

Increasing the number of mental health professionals qualified to work with the service member, veteran and military family population is an entirely different issue. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) has partnered with the Service Members, Veterans, and their Families (SMVF) Technical Assistance Center to develop career pathways into the behavioral health workforce for those who served in the military or area affiliated with the military community. Encouraging more of the SMVF population to enter the behavioral health workforce can address some of the shortages that exist.

Improve Culturally Competent Care

Increasing the number of mental health providers isn’t enough to improve access to care. There is a need for mental health providers who work with veterans to have culturally competent care…to understand the unique aspects of military service. There is a challenge throughout the nation for community providers to be prepared to serve veterans. A 2014 study by the RAND Corporation found that only 23.7% of mental health providers affiliated with TRICARE demonstrated military cultural competence. This is a fact; the number of military culturally competent providers in the community is significantly less than the number of military culturally competent providers in the Department of Defense or Department of Veterans Affairs. That doesn’t mean that there are no military culturally competent mental health providers; just that there are less of them in the community than in the VA or DoD.

The solution is not to send all veterans to the VA, but to improve the cultural competence of the behavioral health workforce. There are a number of ways to do this; PsychArmor has a great series of educational videos that can help mental health professionals working with veterans to better understand them. There are a number of books and publications that providers can use to develop a deeper understanding of these topics, and the Head Space and Timing Podcast is one of a number of podcasts that can help providers understand more.

Reduce Barriers to Care

These two problems…a lack of mental health providers in general and military culturally competent mental health providers specifically…generate a third problem, barriers to care for specific populations. This means that generally the best place for veterans to receive culturally competent mental health care is the VA…but that doesn’t help if the VA is in a high-density veteran population with many treatment seeking veterans. It also doesn’t help if the former service member is not eligible for VA services, like veterans with “bad paper”…discharges that disqualify them for access to VA services. While the VA has increased eligibility for emergency mental health services for veterans with non-qualifying discharges, they have had to necessarily limit those services to a veteran in crisis, and the veteran has to report to the emergency room of a VA hospital…not a clinic, which is much more accessible to most of the veteran population.

Another barrier to care, identified by the VA, is the fact that non-activated Guard and Reserve service members are not eligible for VA care. In congressional testimony in April of 2019, Dr. Richard Stone, Executive in Charge of the Veterans Health Administration, said that “Many of the suicides we are seeing are never activated Guardsmen and Reservists between age 35 and 54 so they are long since their service days.” (Dr. Stone’s remarks at 01:00:50). Just because a Guard or Reserve service member was not called to active duty in a combat zone doesn’t mean that they are not impacted by trauma; a leading cause of PTSD is exposure to natural disasters, and this is one of the core functions of Guard and Reserve troops.

Mental Health Treatment is Part of the Solution

As previously mentioned, this strategy to prevent veteran suicide is one to reduce risk factors. The strategies that increase protective factors are meant to keep a veteran from entering into a suicidal crisis; if they remain connected, have economic stability, and are educated about suicide risk, then there is less of a chance that they will become suicidal. That is only part of the solution, however; there will be times, unfortunately, that either these protective factors are not in place, or they’re not enough to keep a veteran from going into a crisis. When a veteran IS in crisis is when we need to provide them access to responsive care, in order to help them resolve that crisis and get back to a place of stability in their lives. Therapy and mental health treatment is not the only solution to the veteran suicide problem, but it is a critical part of it.

Do you want to help offset some of the costs of the Head Space and Timing Blog and Podcast? Want to show your appreciation and support? You can put some paper in the tip jar by going here or clicking the button below

Want to keep up with all of the Head Space and Timing content? Subscribe Here

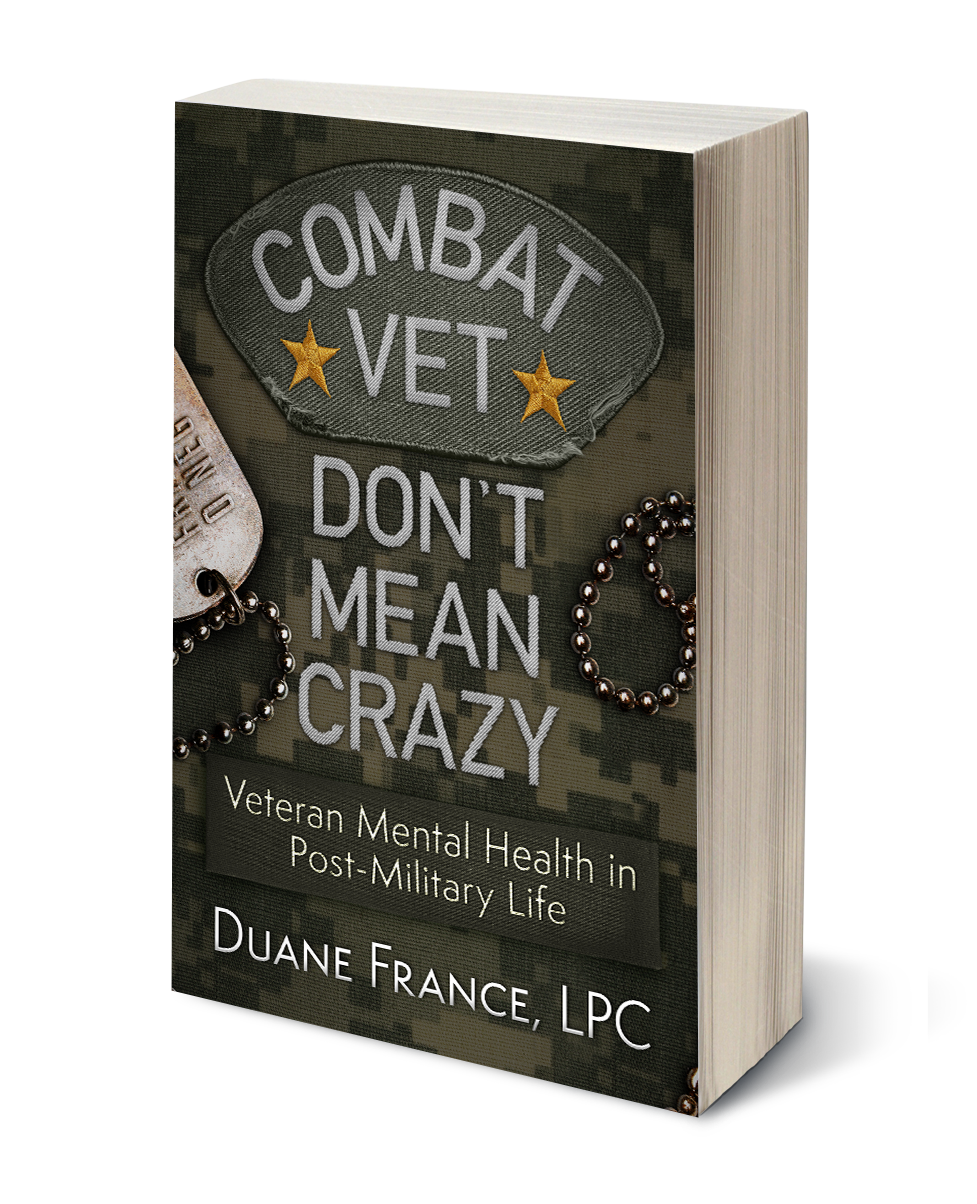

Want to learn more about veteran mental health? Check out the latest Head Space and Timing book

Want to learn more about veteran mental health? Check out the latest Head Space and Timing book

Check out what people are saying about it:

Overall ‘Combat Vet Don’t Mean Crazy’ is a very well written, thought-provoking book. As usual, SFC France did a fantastic job! Being a combat veteran myself who has served in both Iraq and Afghanistan, I feel there’s a lot of powerful information and tools in this book that you can put to use immediately – even as you’re reading this book. Definitely an excellent read on those days of rest and/or distress. – J.C.