This post is an original article written by Eric Milzarski for the We Are The Mighty, a military media brand run by veterans, military family members, and civilians to bring relevant, engaging entertainment to the military community. It is republished here by permission. You can read the original article here. From a mental health professional perspective, it demonstrates the lengths to which a veteran will go to in order to wrap their hands around veteran mental health.

There is nothing more heart-wrenching to veterans with families than having to explain why daddy hasn’t been the same ever since he returned from the war. A reasonable adult can grasp the idea that war is hell and that it can change a person forever, but an innocent kid — one who was sheltered from such grim concepts by that very veteran — cannot.

A. A. Milne, an English author and veteran of both World Wars, was struggling to explain this harsh reality to his own child when he penned the 1926 children’s classic, Winnie-the-Pooh.

As a young man, Alan Alexander Milne stood up for King and Country when it was announced that the United Kingdom had entered World War I. He was commissioned as an officer into the 4th Battalion, Royal Warwickshire Regiment, as a member of the Royal Corps of Signals on February 1, 1915. Soon after, he was sent to France to fight in the Battle of the Somme.

The description, “Hell on Earth” is apt, but doesn’t come close to fully describing the carnage of what became the bloodiest battle in human history. More than three million men fought and one million men were wounded or killed — many of Milne’s closest friends were among the numerous casualties. Bodies were stacked in the flooded-out trenches where other men lived, fought, and died.

This might help give you a picture of just how awful the Battle of the Somme was. Fellow British Army officer and writer J.R.R. Tolkien fought in the Battle and used it as inspiration for the Dead Marshes in The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers. (New Line Cinema)

On August 10, 1915, Milne and his men were sent to enable communications by laying telephone line dangerously close to an enemy position. He tried warning his command of the foolishness of the action to no avail. Two days later, he and his battalion were attacked, just as he had foreseen. Sixty British men perished in an instant. Milne was one of the hundred or so badly wounded in the ambush. He was sent home for his wounds suffered that day.

Milne returned to his wife, Daphne de Selincourt, and spent many years recovering physically. His light finally came to him on August 21, 1920, when his son, Christopher Robin Milne, was born. He put his writings on hold — it was his therapeutic outlet for handling his shell shock (now known as post-traumatic stress) — so he could be the best possible father to his baby boy.

One fateful day, he took his son to the London Zoo where they bonded over enjoying a new visitor to the park, a little Canadian Black Bear named Winnipeg (or Winnie for short). Alan was drawn to the bear because it had been a mascot used by the Canadian Expeditionary Force in WWI. Despite being one of the most terrifying creatures in the zoo, Winnie was reclusive, often shying away from people.

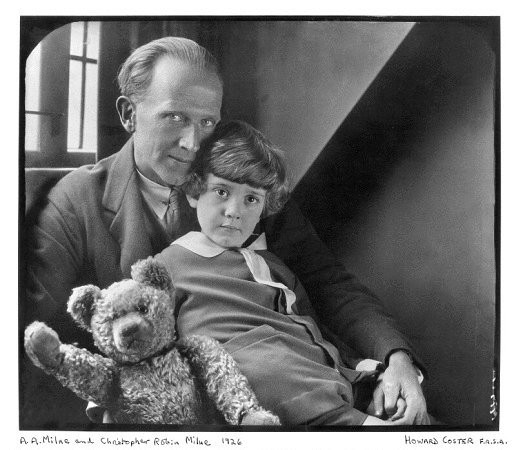

Alan saw himself in that bear. At the same time, Christopher loved the bear for being cuddly and cute. Understandably, Alan bought his son a teddy — the real-life Winnie the Pooh bear.

A.A. Milne, his son, Christopher Robin, and Winnie the Pooh. (Photo by Howard Coster)

The demons of war followed Milne throughout his life. It was noted that when Christopher was little, Alan terrified him when he confused a swarm of buzzing bees with whizzing bullets. The popping of balloons sent him ducking for cover. Milne knew of only one way to explain to his son what was happening — through his writing. A.A. Milne started writing a collection of short stories entitled Winnie-the-Pooh.

It’s been theorized by Dr. Sarah Shea that Milne wrote into each character of Winnie-the-Pooh a different psychological disorder. While only A. A. Milne could tell us for certain, Dr. Shea’s theory seems pointed in the right direction, but may be a little too impersonal. After all, the book was written specifically for one child, by name, and features the stuffed animals that the boy loved.

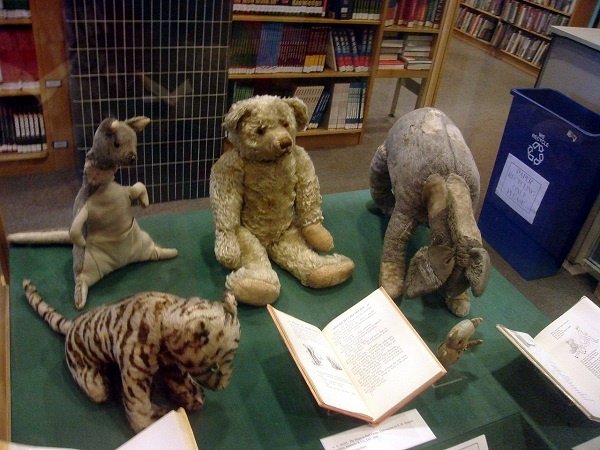

It’s more likely, in my opinion, that the stories were a way for Milne to explain his own post-traumatic stress to his six-year-old son. Every stuffed friend in the Hundred Acre Woods is a child-friendly representation of a characteristic of post-traumatic stress. Piglet is paranoia, Eeyore is depression, Tigger is impulsive behaviors, Rabbit is perfectionism-caused aggression, Owl is memory loss, and Kanga & Roo represent over-protection. This leaves Winnie, who Alan wrote in for himself as Christopher Robin’s guide through the Hundred Acre Woods — his father’s mind.

It all kind of makes you think about that line Winnie’s says to Christopher, “If you live to be a hundred, I want to live to be a hundred minus one day so I never have to live without you.”

(New York Public Library)

The books were published on October 14, 1926. As a child, Christopher Robin embraced the connection to his father, but as the books grew in popularity, he would resent being mocked for his namesake character.

Christopher Robin Milne eventually followed in his father’s footsteps and they both served in the Second World War. His father was a Captain in the British Home Guard and he served as a sapper in the Royal Engineers.

It was only after his service that he grew to accept his father’s stories and embraced his legacy, which endures to this day.

In fact, Christopher Robin, a film starring Ewan McGregor and directed by Marc Forster (known for Finding Neverland), is in theaters now. Be sure to check it out.

Eric Milzarski is a U.S. Army veteran and was deployed to Kandahar, Afghanistan with the 101st Airborne Division where he served as a radio operator. After being honorably discharged, he then pursued a career in the film and television world.He is now the resident “nerd” at We Are The Mighty.

Eric Milzarski is a U.S. Army veteran and was deployed to Kandahar, Afghanistan with the 101st Airborne Division where he served as a radio operator. After being honorably discharged, he then pursued a career in the film and television world.He is now the resident “nerd” at We Are The Mighty.

1 Comment

Nicole Johnson · August 22, 2018 at 2:36 pm

Brilliant ..and spot on. I never realized the incredible story behind the book. What a powerful and moving message. Nice work, as always.

Comments are closed.