For veterans, their time in the service really was both the best and worst of times. Their time in combat, even more so. Dickens had it right; like many fundamental truths that seem to be around, this one resonates.

In a previous post, I talked about what PTSD is: a diagnosable mental health condition that meets certain specific criteria. With a rate of anywhere from 11-20% of veterans meeting this criteria, not all veterans have PTSD…but that does not mean that the remaining veterans are not struggling with some form of adjustment or difficulty resulting from their military experience.

Many of the veterans that I talk to understand what I’m saying; they wish those who were not in the military were able to understand this as well. Serving time in the military is very much like immersing yourself into a different culture. The military has it’s own expected standards of conduct, it’s own spoken and unspoken rules, and even it’s own language. It would be as if someone who grew up in Iowa, for example, went to live in England for twenty years, then returned to Iowa. Their personal experiences, their character, would develop by total immersion living in a different culture. It will take some time for that individual to adjust back to a different culture…even more so if they loved living in England.

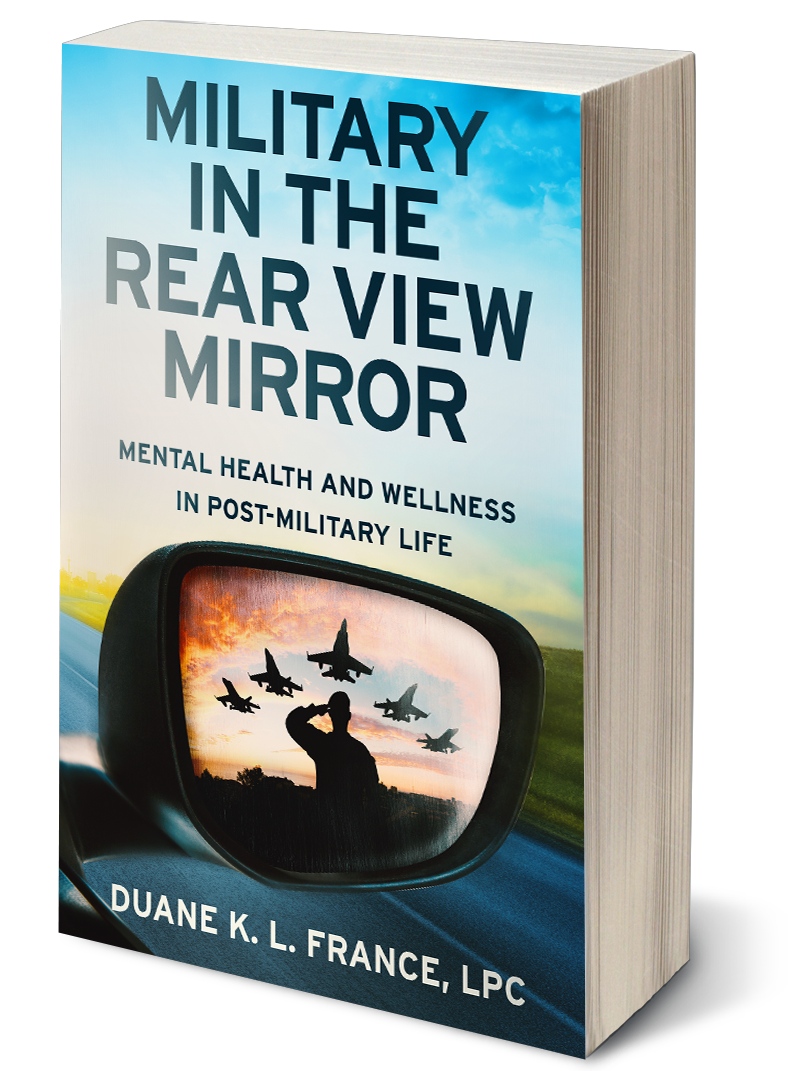

So veterans struggle with returning to civilian life after the military. Why? What is the problem with just picking up where we left off, using all of the skills that we learned to make a better version of the eighteen-year-old self that joined the military? Because there is something that is fundamentally satisfying about a veteran’s time in the service. They meant something. I knew 25-year-old supply sergeants who were responsible for millions of dollars worth of inventory…who then got out of the service and found it hard to find a job. I knew 28-year-old officers who were responsible for the lives of over 150 soldiers in a combat zone…who then found it tedious to work in a bank. For some veterans, what we were is so much better than what we are…and that’s a difficult concept to consider. If we latch onto that idea, like so many veterans do, then we will be forever looking backwards at the best days of our lives, rather than forward to the rest of the days of our life.

Complicate that with the fact that the “best days of our lives” were often pretty bad. Out of my five deployments, my first to Afghanistan was the worst, with my deployment to Iraq making a pretty good case for itself; however, I look back at my time in RC East with fondness, pride, grief, and, yes, pain. I tell funny stories about the time a pack of donkeys was weaving in and out of our security patrol, calls of “Donkey passing on the left” going out over the platoon net. I tell stories of skill, bravery, honor, and courage. When the discussions about women in combat start, I talk about my driver, one of the bravest women I know, dismounting the vehicle behind me just to watch my back. I tell stories of monkeys, MREs, stupid movies that were watched over and over again, and remember the beauty of the country.

Veterans talk less often about the other stuff, the hard stuff…but think about it more often. The bad comes just as often as the good, if not more so. A veteran does not have to have PTSD to experience grief at the loss of a buddy, or frustration at the fact that they find it difficult to readjust to society. When veterans leave the service, many of them feel as though they have lost their sense of purpose. They were once counted on, depended on, they were good at what they did and they loved it. They were important…and losing that sense of accomplishment, that sense of importance, is very difficult.

Think about the inspirational speeches that you have heard throughout the years: the Saint Crispin’s Day speech from Henry V, Patton’s speech to the Third Army (warning, if you want one, because Patton could be a bit…vulgar), or Theodore Roosevelt’s Man in the Arena speech. If you’re a veteran, and you’re like me, something stirs inside of you at the thoughts and ideas presented here. The sound of Taps, while painful, is also beautiful. The sound of Amazing Grace, played on bagpipes, is simultaneously one of the greatest and worst songs in the world.

Just because a veteran does not have PTSD does not mean that they are not struggling…taking the time to understand that struggle, and to hear a funny (or not so funny) story, can lift the burden just a little bit.

Thanks for joining me in the conversation to raise the awareness of what veterans experience. Please, forward this to your networks, make comments, share this with anyone who you think may understand just a little bit better what veterans are going through. Maybe, in this small way, we can support those who sacrificed more than can be imagined for those who may never know.

1 Comment

Let's Talk About Veterans for a Minute | Head Space and Timing · August 20, 2016 at 6:47 am

[…] Combat: It Was the Best of Times, It Was the Worst of Times. This article describes some of the meaning behind Martin Sheen’s comment in the beginning of Apocalypse Now: “When I was here, I wanted to be there; when I was there, all I could think of was getting back into the jungle.” […]

Comments are closed.