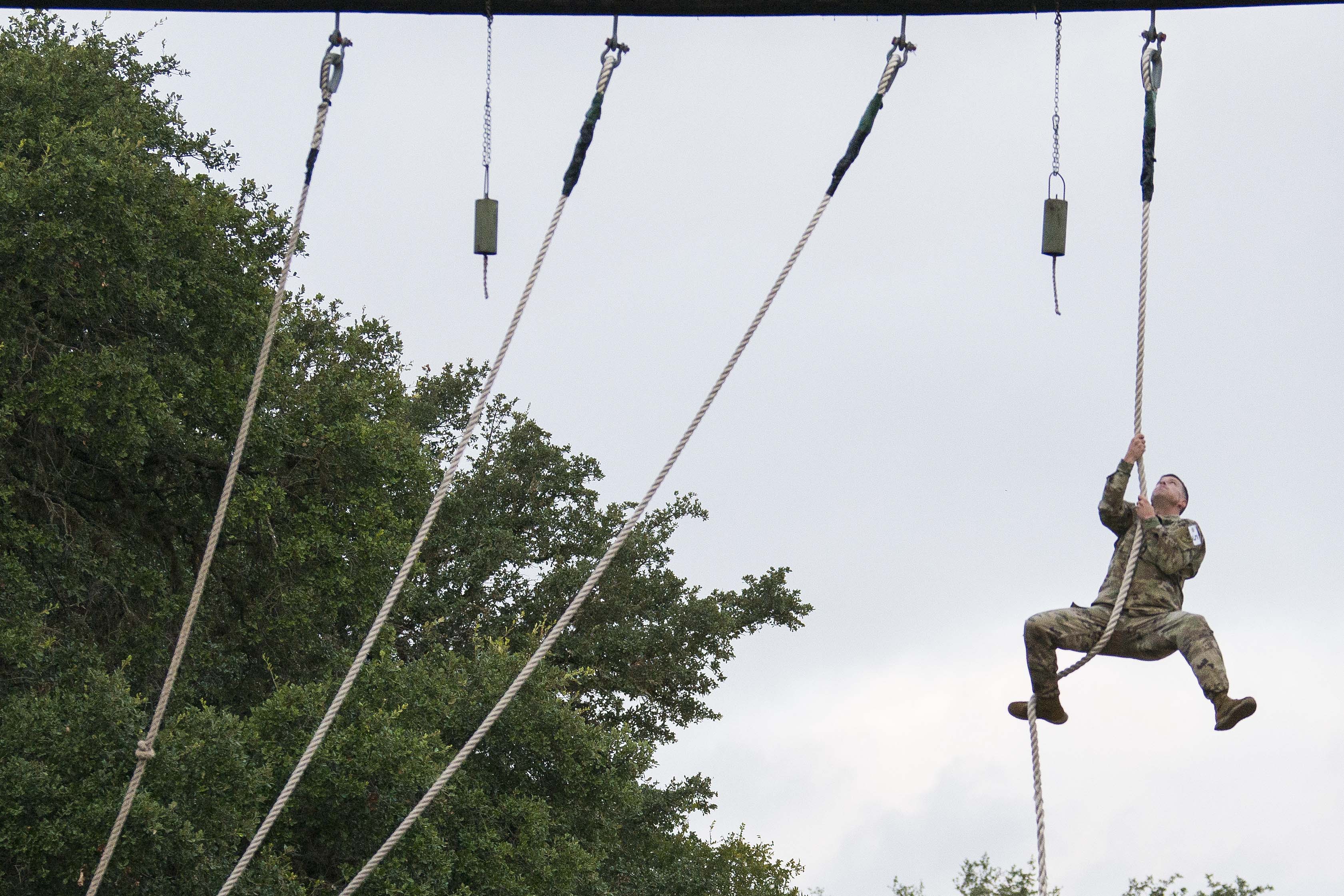

U.S. Army Staff Sgt. John Cauthon climbs a rope on an obstacle course during the Drill Sergeant of the Year Competition August 19, 2019 (U.S. Air Force photo by Sean M. Worrell)

In my experience…and this is as much personal experience as it is observation…veterans tend to underestimate their own abilities and capacities. Whether it’s because the military is a collective culture where there is a set parameter of “acceptable” behavior, or because of the evaluative nature of the military, we are and can be extremely self-critical.

Maybe it’s because many service members internalize the values that the military attempted to instill in us. Selflessness, sacrifice, individual effort is for the benefit of the whole rather than the individual. In the military, the concept of “my shield covers my brother and sister” is one that carries into other aspects of our lives. Praise is deflected; leaders point to the efforts of their subordinates, troops point to each other when asked which is the bravest, the most worthy. There are exceptions, of course, like there always are, but this is a character trait that I have seen in many veterans.

Self-confidence Becomes Arrogance

It’s almost as if our evaluation of what is acceptable slips a couple of notches. If we measure arrogance, healthy self-confidence, and humility on a scale, arrogance would be a ten, self-confidence a five, and humility a zero. For many of us, the scale drops…arrogance becomes a six, so that if we express what is generally considered self-confidence, it is approaching arrogance. We don’t want to brag, when all we’re really doing is accurately describing what we have the ability to do. That means that what we see as self-confidence is really borderline humility, and what we consider humble is down the charts.

This could be a source of discomfort with being told “thank you for your service,” especially in the younger generation of veterans. “Just doing my job” is a typical response that many have to that phrase.

Comparison and Competition

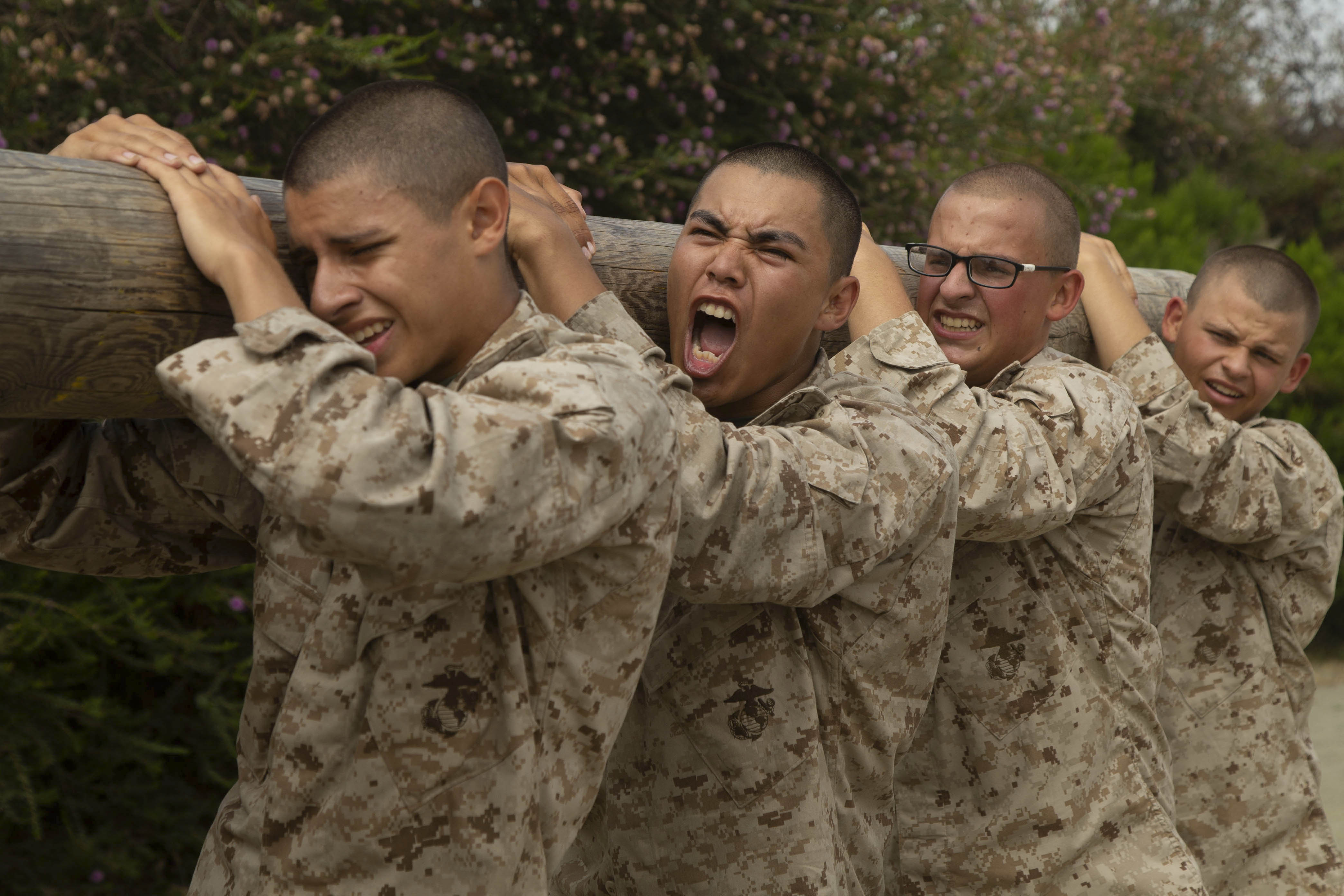

Another possible source for a shift in self-worth is the pervasive nature of comparison and competition in the military. Service members are very literally ranked in comparison to those around them. One glance at someone’s uniform lets them know where they stand in the hierarchy of the military compared to someone else…and, often, that extends not just to people of different rank, but who has been one rank longer than someone else. Who has more “time in grade” is something that many people know, because that conveys a certain perceived level of competence, either good or bad.

Another aspect of the military is the inter-service and intra-service rivalries that abound. We cut each other down as much as any college football rivalry. For paratroopers, those who are not Airborne qualified are “dirty nasty legs.” Service members who serve combat occupational specialties versus those who serve in support specialties. Those in support specialties who serve with combat troops, versus those who didn’t. Those who have deployed to combat, and those who haven’t. It’s as if the entire military experience is measuring where I stand in relation to others, and it’s hard not to internalize that sense of comparison.

Explanatory Style

Explanatory or Attributional Style is a way that we describe the meaning of events to ourselves. It’s how we explain what happens, and we can apply both positive and negative explanatory style. The concept of explanatory style emerged from the work of Martin Seligman and helplessness theory. There are three domains of explanatory style: personal, permanent, or pervasive. Personal explanatory style is the length to which someone describes an event as having an internal or external cause; if something bad happens, it was either bad luck or my fault. If something good happens, it was either my skill or a fluke. For some veterans, we apply a negative personal attribution to positive events…we dismiss it as due to external factors, not our own ability.

Consider this scenario: a service member leaves the military. College is paid for, so they go back to school, but I’m not really sure if I can do it. High school was so many years ago, I probably forgot everything, right? Besides, school ain’t for me. In spite of that, I doubtfully move forward, anticipating failure and expecting the worst. But…it actually seems easier than I thought. Can this be true? Nah, I must have just lucked out and got an easy class. Well, I’ll keep going…and end up on a roll. Dean’s list. 3.8 GPA. Something in the back of my mind, however, is certain that the next class is going to be the one that kills me, imposter syndrome is going to kick in and someone is going to bust through the door and shout, “what are you doing here?” Then everyone is going to know I’m a phony.

When Not Enough becomes Too Much

As I mentioned before, this doesn’t apply to all veterans. We are not all one single homogenous group that thinks and talks the same. We all know people who’s arrogance scale has slipped the other way, those that seem to believe that their military service entitles them to a higher status than those who never served. That attitude is as unhelpful as the other type of attitude…”me, me me” all the time is as imbalanced as “them, them, them” all the time. We have to be careful not to get TOO full of ourselves, just as we have to be careful not to sell ourselves too short. Like with everything, balance is key.