This post was originally posted as part of the American Counseling Association Blog Project. Original post can be located HERE

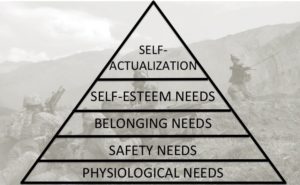

In a continued effort to expand the topic of veteran mental health beyond PTSD and TBI, I thought that I’d give a deeper look into the mindset of the former military service member by looking at how veterans meet their needs according to Abraham Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. Maslow’s conceptualization is well-known, not just in the mental health professional and academic community but in many other areas as well: workplace, conflict resolution, learning, and many more. As mentioned previously, it’s not my intent to rehash what those needs are, only how they are met.

I realized some time ago that it’s not just about what needs we purse, but how we pursue them.

For those unfamiliar with the military, a large portion of the lower needs on Maslow’s hierarchy are provided for the military service member with little effort on their part. If we look at physiological needs, such as food, drink, and shelter, those needs are satisfied nearly immediately. Upon reporting to Fort Leonard Wood for Basic Training in 1992, after the Army gave me the same set of clothes and the same haircut as everyone else, they also gave me chow. They gave me a blanket, a bunk, and a locker to put my stuff in. Granted, the blanket was one of those scratchy green things and the building was built sometime during WWII, but my needs were met. And that continued throughout my military career; if you were single, you could eat at your unit’s dining facility for free. If you were married, the military gave you extra money to pay for the food at the dining facility. If single, you were given a barracks room at the end of your first day at your unit; if married, you could probably get an apartment or townhome for your family within a week, and the military would pay for your hotel in the meantime. Granted, they may not have been the best accommodations, but you were housed and fed. No questions asked.

Next up the hierarchy, safety needs: security, order, stability. No question that the veteran had that, or mostly had that. It is extremely difficult to “get fired” (be discharged) from the military service, so there is little danger in abruptly losing your job, unless you violate the rules in some extreme way. Every month, the first and the fifteenth, you get paid. Again, there are always exceptions, but in the overwhelmingly vast majority of cases, the service member knows with confidence when their next paycheck arrives. The military runs on discipline and structure, so the military service member fits right into a routine that has been going since before they got there and will continue well after.

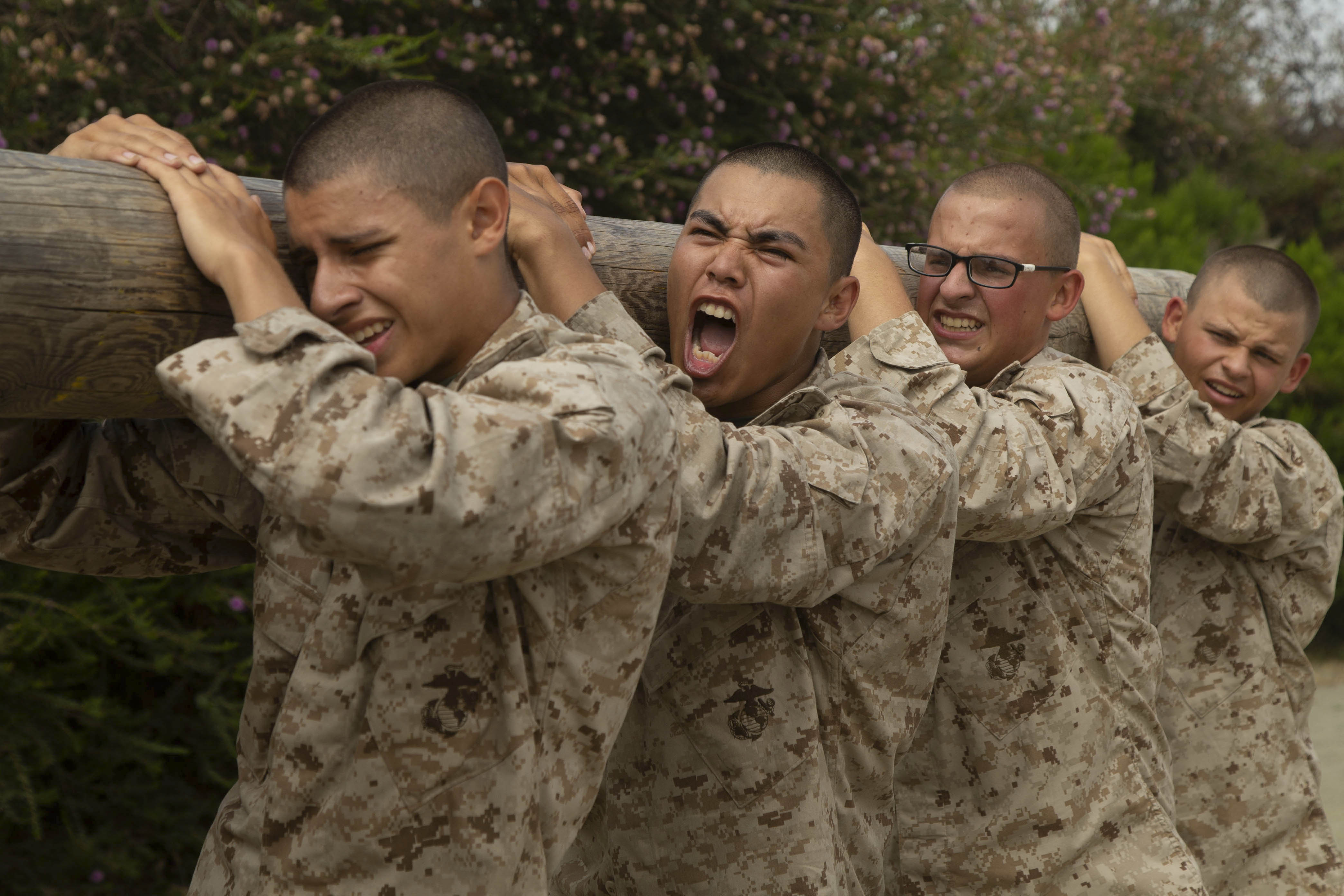

The belonging needs are also a major aspect of a veteran’s military service. The bond that is created through shared hardship is well known: Band of Brothers, closer than family. There’s something about an old Army buddy that is unexplainable…you can travel across the country and sit on a porch and laugh (and cry) about old times, without skipping a beat. These are mutually supportive and beneficial relationships; they have to be, because during times of stress, those you serve with need to be trusted and relied upon.

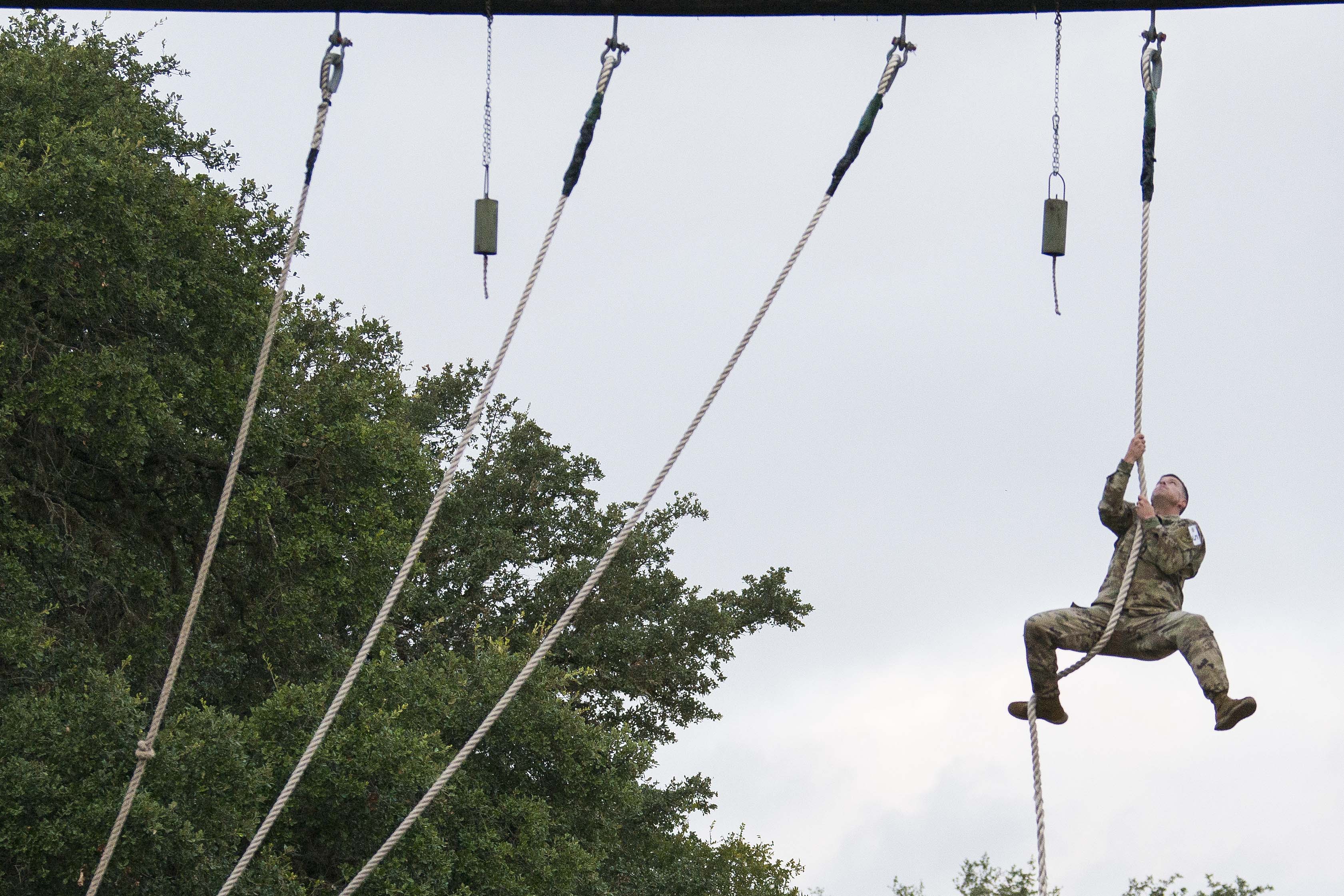

Next, esteem needs: self-esteem, achievement, mastery. The military provides a nearly infinite amount of opportunities to stretch you beyond what you think your capabilities are. Obstacle courses. Jumping out of airplanes and rappelling out of helicopters. Enduring harsh environmental conditions without permanent harm. Learning how to suffer. Each of these things provides a level of resilience that is supported and strengthened by the encouragement of your friends and buddies around you. During one particular day in November or December of 2008, one of my Soldiers said to me, “Twenty years from now, I’m going to be telling a story about how my bald-headed platoon sergeant made us ruck march through a blizzard.” It was snowing pretty heavy at the time, but calling it a blizzard was a bit of an exaggeration. I hold that veteran in esteem, and I know that he held me in esteem then and still does now…because my Platoon Leader and I were right there with them. These kinds of events help the service member build mastery and confidence, and give them a sense of achievement.

And finally, self-actualization. Maslow famously thought that few would actually reach this level of true fulfillment of their actual potential; however, there is a level of personal satisfaction that many service members have about their military career, they often engage in personal growth, and have peak experiences that could often approach self-actualization.

Then…they leave the military.

Don’t get me wrong, I don’t mean to imply that military service is a form of constructed or artificial environment that is designed to meet the service member’s needs in some way. I imagine that any type of formative environment can find parallels in these examples. My point is that veterans, once they leave the service, are used to having their needs met in one particular way, and now have to learn how to meet those needs in a different way.

Once a veteran has obtained a sense of achievement and mastery in their chosen profession, the military, they then have to pivot to developing mastery in an entirely different arena. A young Marine who led a team in Afghanistan is given the opportunity to lead their own crew for a roofing company, and experiences significant stress because they believe that failure equates to loss of equipment or, even more importantly, loss of life. A Navy Armament Technician who excelled at building explosive ordinance might struggle in an office environment; even though the task is not challenging, it’s unfamiliar, and they’re not used to not performing tasks well.

Belonging needs? Many veterans feel a sense of alienation from their families and their communities. The only ones to “get them” are their buddies, and they’re no longer around. The bond that is built through shared hardship is not built when no hardship exists. Veterans also learned that, in the military, their peers and superiors were very much a part of their lives 24/7, 365. But when the whistle blows or the clock strikes 5, the veteran’s interaction with their civilian supervisor comes to an end. This also leads to a level of disconnectedness and feelings of loneliness.

Continuing back down the hierarchy, to safety needs. PTSD not withstanding, in which veterans often feel as though they don’t feel safe anywhere, stability is a huge factor for veterans. I’m on my second job since retiring in 2014. I’ve talked to other professionals, those who had a “successful” transition, in which their first job lasts eighteen months or two years. A colleague of mine, a retired Air Force pilot, has had four different positions with three different agencies, and is about to transition to a fourth, all in the last five years. The stability that the veteran once knew when they were in the military is no longer guaranteed, and that loss of stability can be staggering.

Finally, the safety needs. The crisis of veteran homelessness is well-documented. A family of five is no longer provided housing at the government’s expense; they are at the mercy of the local housing market regarding availability and price, and depending on where they are, $1,200 a month for a housing budget does not give them the ability to find shelter. Food is no longer provided. The basic physiological needs, which were once unquestioned, are now unsatisfied.

Don’t get me wrong. All humans make choices; we live beyond or means, we choose fast and unhealthy over the deliberate and healthy. We choose the path of least resistance; we cope with stress in unhealthy ways rather than the alternative. The point here is that, often, veterans are unaware of how their former method of meeting Maslow’s needs are no longer effective, and that leads to frustration. I’ve talked to veterans who feel as though they are starting over at ground zero, that their military service was meaningless.

If you are a family member or community member supporting a veteran, please take the time to consider how much of a change it can be for a veteran transitioning out of the military or returning from combat. It’s not just about getting a job or finding a house; it’s about understanding how much of a fundamental shift is required for a veteran to meet the basic human needs that we all desire to have fulfilled.

If you’re a veteran, and you’re reading this, what you’re going through is 100% normal. It’s to be expected. You were once confident, competent, stable, and safe, and you can be all of those things again…you just have to be aware of your own capabilities, and learn new tricks to go along with the old ones.

2 Comments

The Challenges of Veteran Mental Health: Beyond PTSD and TBI | Head Space and Timing · February 4, 2017 at 11:27 am

[…] Another concept that applies to veterans is needs fulfillment, as described in another one of those old Pysch 101 standbys, Abraham Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. Rather than focusing on whether or not those needs are met, HOW they are met is a struggle for some veterans. Returning from an environment that is extremely validating, provided the veteran puts forth the effort, a veteran must learn that the manner in which their needs were satisfied in the military and especially during combat is not comparable to the manner in which they need those same needs met in the “civilian world.” Physiological needs were often never questioned, as they were often provided to the service member: food, water, these things were readily available, if not always pleasant or palatable. Safety needs? Respond with aggression. Create safety where none exists. Belong/sociological needs were developed within a brotherhood that resulted from close proximity and shared experience…which breaks down quickly upon returning from combat, and is nearly nonexistent when the service member leaves the military. As we climb the pyramid of Maslow’s needs, the veteran experiences frustration and anger because the manner in which they formerly met these needs is no longer effective, even though they want them to be effective, because they worked, and the veteran was good at it. A look at how veterans need to learn how to satisfy needs in a new way can be found here. […]

Why Veteran Mental Health — Head Space and Timing · July 5, 2018 at 6:05 am

[…] That person is not also having to contend with Moral Injury. Or having to figure out how to meet their needs after leaving the military. The repeated stress of multiple deployments and the strain that it has […]

Comments are closed.