Soldiers advance through snow to their next firing position, March 18, 2017. Army National Guard Photo by 1st Lt. Benjamin Haulenbeek

In any community, people speak in lowered voices about the place that people go when they’re in psychological distress. It’s derogatorily called the “loony bin” or the “nuthouse.” The conversation gets chill and people quickly change the subject when you hear of someone who went to the local psychiatric hospital. We don’t react that way if someone is admitted to the hospital, of course. Then, it’s sympathy and get well cards and “how can I help?”

Just like any other cultural group, the military population is no different, and possibly worse. The stigma against seeking help for psychological distress is strong in the mitiary and veteran population. We talk about sending someone to the “fourth floor” (several psychiatric units on military bases are on the fourth floor of the base hospital). People who experience a crisis are somehow seen as weak or deficient in some way, and treated as such.

The simple truth is, military service is inherently dangerous, and with danger comes psychological stress. With psychological stress comes the need to address it. The military community will not effectively address it without reducing the stigma against seeking help.

A 2014 study by the RAND Corporation identified a number of priorities in developing stigma programs. A significant focus is for organizations to move beyond reducing stigma to increase treatment-seeking behavior.

Decrease the Impact of Stigma

The first strategy to increase treatment-seeking behavior is to reduce the impact of stigma itself. Webster’s dictionary defines stigma as “a mark of disgrace associated with a particular circumstance, quality, or person.” As long as seeking help for psychological distress is seen as disgraceful, then it will be stigmatized. Stigma itself is inherently isolating, causing someone to either withdraw from others or be separated by them. The sense of isolation only increases the impact of stigma. It’s important to understand that by marginalizing someone for seeking treatment, the sense of disgrace is alive and well.

Cultural Change

Another strategy to increase treatment-seeking behavior and reduce stigma is to change the culture against seeking help. Admittedly, there is a “suck it up and drive on” aspect to military service. This causes many service members and veterans to avoid seeking medical treatment for physical injuries. This is even more pronounced for psychological concerns. There has been a cultural shift over the past fifteen years. This is likely due to the fact that the psychological impact of military service is undeniable. The suicide rate among service members, veterans, and their families is increasing. Senior leaders in the mitiary are speaking out about their own mental health experiences. Courageous people are starting to stand up and say, “look: it’s okay to not be okay.”

Increase Peer Support

A key factor in making it more likely that service members will speak out about their mental health challenges is to increase peer support. One study showed that veterans apply stigma differently to themselves compared to how they apply it to other veterans. In other words, we think that others will find it disgraceful for us to seek treatment, but we will not find it disgraceful for others to seek treatment. Peer Support is critically important for members of the military affiliated community to understand that they’re not alone, that there’s nothing wrong with seeking treatment.

Along with this, however, we must understand that peer support needs to be effective. We can’t care for someone if we’re not healthy ourselves; anyone working with psychological distress needs to be trained in a basic level of mental health awareness, confidentiality, suicide prevention, boundaries, and a number of other aspects when it comes to mental health. Simply experiencing the condition and feeling better doesn’t automatically make one an effective peer.

Change Perceptions about the Effectiveness of Mental Health Care

Another strategy to increase treatment seeking behavior is to change how the military community perceives the effectiveness of mental health care. This is something strange that I’ve noticed when it comes to veterans and therapy. Negative experiences apply to all therapy, but positive experiences are contained to a single instance. Bad experiences with therapy are considered the norm, with good experiences the exception. If a veteran has a bad experience with one or two therapists, they they go back to their friends and say, “therapy sucks. Don’t bother. It didn’t work, it’s garbage.” If they happen to have a good experience, however, they go to their friends and say, “you should go to THIS therapist. Most therapy is crap, but THIS ONE is a good one.”

We need to change that around, so that good experiences with therapy are considered the norm, with bad experiences the exception. Mental health professionals have a role to play in this, of course. We have to ensure that we are providing effective care in the best way possible, and minimize the negative experiences…but the military affiliated community also has a role to play in it.

Reduce Barriers to Care

Finally, we must make a concentrated effort to reduce barriers to seeking mental health care. This is as big a challenge as the rest of them; the affordability, availability, and effectiveness of care must be addressed. Mental health professionals are health professionals just like a dentist or a doctor; however, insurance does not adequately cover mental health treatment. Many veterans and their families do not have access to adequate insurance to meet their needs. The effectiveness of care must also be addressed. Mental health professionals who do not understand military culture but treat military service members is a significant barrier to care…this goes back to the good experience versus the bad experience to treatment.

For a community to effectively address stigma against help seeking, there must be a concentrated effort to improve the way we encourage service members, veterans, and their families to access effective care. How can you make a difference?

Sign Up for Updates

Subscribe to get added to our content distribution list, and each week you’ll receive our newsletter that contains links to our weekly video, blog, and podcast.

Do you want to help offset some of the costs of the Head Space and Timing Blog and Podcast? Want to show your appreciation and support? You can put some paper in the tip jar by going hereor clicking the button below

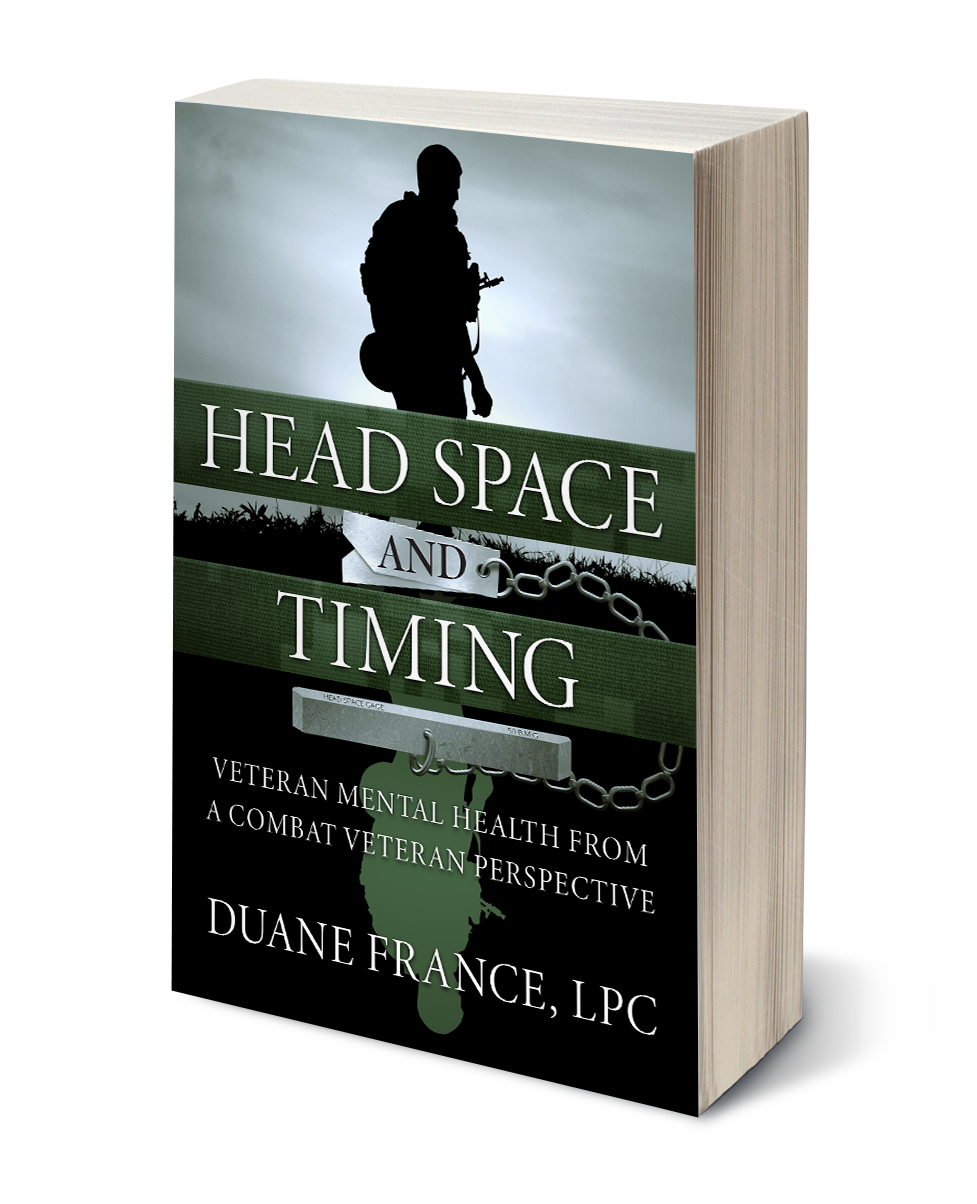

Want to learn more about veteran mental health? The first HS&T Book has recently been released in paperback. Click on the image to the left or this link to purchase the book. See what people are saying about it: This compilation of Duane’s work is key and essential to anyone working with Soldiers and Veterans. Duane provides a senior NCO’s perspective with unmeasurable experience and knowledge on top of his natural gift for seeing numerous levels of humanality and the challenges faced by those who have served our country. I highly recommend it! – A.C.

Want to learn more about veteran mental health? The first HS&T Book has recently been released in paperback. Click on the image to the left or this link to purchase the book. See what people are saying about it: This compilation of Duane’s work is key and essential to anyone working with Soldiers and Veterans. Duane provides a senior NCO’s perspective with unmeasurable experience and knowledge on top of his natural gift for seeing numerous levels of humanality and the challenges faced by those who have served our country. I highly recommend it! – A.C.

1 Comment

Nelson Ormsby, Callsign CavDad · October 9, 2019 at 2:04 pm

As an outsider having had the privilege of gaining access to your culture, the stigma and barriers associated with getting help perhaps no greater than with PTS? Does it perhaps start, or at least pivots in some ways, with the “D” on the end of “Post-Traumatic Stress“? Intuitively, labeling the hyper-vigilance which helped keep you alive in the battle space a “disorder” misses one of the essential realities of how PTS as suffered by civilians, after say a major surgery or sexual assault, different in certain key respects from that experienced by those raising their right hand? If you broke your leg, would you be expected, and more importantly, how might you expect it of your self, to crawl in a corner and heal yourself? In sum, might a significant stigma, as well as personal and institution barriers to seeking treatment, be better addressed by adopting an injury model, and calling PTS an “injury” as opposed to a “disorder”? Please further educate the tree-hugging civilian I am. Any shortcomings rests with me, your pupil, and not the teacher!

Comments are closed.