The 82nd Airborne Division Advanced Airborne School Jumpmaster Course is three weeks long.

It took me six months to complete it.

There’s not a leadership course that doesn’t talk about the lessons that can be learned by failing. Failure lets us know that we’re not perfect; it helps us understand how not to get the job done, and builds resilience and perseverance. I’ve screwed up more times than I can count, but when asked about one of my biggest failures in my military career, I always point back to this one. There are some pretty big lessons that I learned during that year, ones that have stuck with me nearly twenty years later.

Sometimes the best goals are the ones other people give you

I didn’t want to be a Jumpmaster. Not really, not at the beginning. I wasn’t alone in that, either; you didn’t get any extra money for it, and Jumpmasters were always running around doing stuff while Joe put on their parachutes and then took a nap waiting to load the aircraft. No, I was in a unit with a large number of Noncommissioned Officers, but few Jumpmasters.

Our First Sergeant didn’t like this. In the summer of ’99, our unit had two Jumpmasters, and it was supposed to have six. So he decided to assist in obtaining the motivation to serve the unit, rather than serve ourselves.

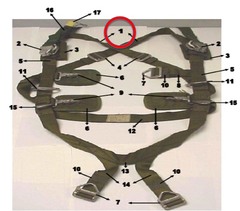

To get into Jumpmaster School, you had the pass the Jumpmaster Pre-test. This is a written test on the proper nomenclature of every  item of equipment on a parachutist’s rig, and then a rigging test in which you had to properly assemble a rucksack, a release harness, and a lowering line. The written test is a 25 question test, but there were something like 150 (or more) different variations.

item of equipment on a parachutist’s rig, and then a rigging test in which you had to properly assemble a rucksack, a release harness, and a lowering line. The written test is a 25 question test, but there were something like 150 (or more) different variations.

Our First Sergeant, in order to establish the appropriate motivation, decided to hold weekly Leadership Development courses. This was held on a Friday. After all of the Soldiers had been released. Starting at 1700 (5PM). First, we would all be in the conference room, and have to take the nomenclature test. Not the 25 question test, but the 150 question test. After that, we would be required to go outside and take the rigging portion of the test. This would typically take an hour, maybe more if a bunch of us screwed it up…which we did. Weekly.

The only way to get out of this torture was to take and pass the Jumpmaster Pre-test…we would then be excused from the weekly “leadership development.” Needless to say, I started studying my butt off, and took the Pre-test just to get out of the weekly training…which, I am certain, was the whole point

Sometimes the goal you’re aiming for isn’t the goal you need

At about the same time, the 82nd had a bunch of slots to go to Pathfinder school. I may not have wanted to go to Jumpmaster school, but I sure wanted to go to that one! I had a mentor who was a Pathfinder, and it was my goal to eventually get to Fort Campbell. My uncle had been in the 101st in Vietnam, it was close to family, and…truth be told…another badge wouldn’t look too shabby, either. What can I say, I was young and stupid.

So not only was my First Sergeant the master of the stick, he was also the master of the carrot. As we started getting our names in for Pathfinder school, the old man decided, “well, Pathfinder school does nothing for the company. It’s good for you, but we’re not going to use it. Nobody’s getting on the list to go to Pathfinder School until you go to Jumpmaster School.”

That was it for me. I passed the pre-test. I had the incentive to go. I might as well make it happen.

Running into a brick wall only makes you want it more.

When I went, and it’s probably the same now, Jumpmaster school was broken up into three weeks. The classroom portion, the Jumpmaster Personnel Inspeciton (JMPI), portion, and the Aircraft portion. I did pretty well in the classroom portion, but…like many, many other aspiring Jumpmasters…the JMPI portion was my downfall. If I remember correctly, you had three chances to pass the test.

You have to inspect three jumpers within five minutes, not missing any deficiencies identified as “major” and only two identified as “minor.” With each successive NoGo, my frustration level increased…as did my desire to succeed. After being dropped from the course, I returned to my unit, frustrated and defeated. The only question from the ever-present First Sergeant:

“When are you going back?” By that time, I was all in. Wild horses couldn’t have kept me away.

Maintain awareness, or you might miss success.

It took another cycle for me to get back into the course. I had practiced my JMPI sequence in the meantime; my First Sergeant knew some people who packed the parachutes, so we got an extra one and rigged up a Soldier so we could practice. We gave him some comp time, and I got some practice time. I hesitate to say it, but I also bent the rules a little bit by taking the parachute home with me. What are you going to do, kick me out of the Army? Like many Airborne wives, my beautiful and long-suffering wife allowed me to have her put on the parachute and practice my JMPI sequence at home!

Now I’m back. My motivation has been established, my failure smacked me in the face, and I never wanted anything more than I did at that time. When you come back into Jumpmaster school, you don’t get three chances, you only get two…and I needed both.

There I was, on the edge of failure again. I remember it plain as day…I was testing in between Bragg’s famous 34 Foot Towers, and when I completed my last Jumper, I stood there frozen. Did I miss anything? Did I not make it in time?

“Jumpmaster, move in front of the second Jumper,” the Jumpmaster Instructor said. My heart sunk. I couldn’t believe it…I was on the outer edge of my recycle window, if I wanted to come back I’d have to do the whole course again. I moved in front of the second jumper.

“Take a look at his reserve parachute, Jumpmaster,” he said. At this point, I knew I was trashed. The only thing that could have been wrong with his reserve was a major malfunciotn, which means I missed it, and failed. “What do you see?”

I bent over, gripping the reserve parachute so hard that it, and the guy wearing it, was shaking. I’m surprised the heat from my gaze didn’t make the thing catch fire. “What do you see, Jumpmaster?” He said again. Through clenched teeth, and an angry haze directed at my incompetence, I finally told him, “I don’t see anything, Jumpmaster.”

“That’s good,” he said behind me. “That’s because there’s nothing there. JUMPMASTER.” At that moment, it hit me that he’d been calling me Jumpmaster the entire time…I’d passed!

When I stood up, I’m not sure if he thought that I was going to crack him one or give him a hug. To this day, I’m not sure which one I was going to do, either. I stood there staring at him, while the three yahoos I was inspecting were laughing at me. I probably had the goofiest grin plastered across my face, and he said, “Get out of my testing area, Jumpmaster!”

I must have set a land speed record back to the classroom. You could tell which of us made it, and which of us didn’t, and I was glad to be on the side of those that had.

It was the most challenging school I attended in my 22 years, and rightfully so. It wasn’t something to play with, and people’s lives were literally at stake. From among any accomplishment in my career, the abilty and responsibility to be a Jumpmaster is the one I’m most proud of.

And I didn’t even want to do it in the beginning.

Enjoy this post? Get more like it by subscribing to Head Space and Timing on Messenger