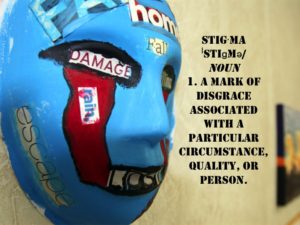

There has been much discussion over the past fifteen years about the stigma of mental health with veterans and active duty service members. A recent report by the Government Accountability Office, which consists of results obtained from 23 focus groups at six locations, indicates that the stigma against mental health is alive and (un)well in the Active Duty Military.

In my experience in working with veterans, stigma exists in two separate areas: the external stigma, which is made up of the collective understanding about veteran mental health in the installation or community, and the internal stigma, the understanding about veteran mental health within individuals. The individual opinion regarding mental health certainly drives the external opinion, and the prevailing impact of the community opinion certainly influences individual opinions.

There are institutional policies that perpetuate the stigma, without intending to do so. Several years ago at my local installation, during the post-deployment processing, those Soldiers identified as needing to see mental health for more in-depth screening were given purple folders, and very quickly everyone knew what these purple folders symbolized. In the GAO report, service members at one installation said that a single elevator accesses the mental health clinic on post, so anyone getting into that elevator is known to everyone else to be seeking mental health. One participant described it as the “elevator of shame.” Gotta love the bluntness of the military service member, but you know that this description is widely known at that post.

I have had discussions with individuals who have said, “No, we’re doing a lot to change that. I mean, Colonels and Sergeants Major openly admit to going to mental health now, it’s common.” I grant that, there are a lot of higher-ranking individuals going out of their way to make it widely known that they personally don’t have a stigma against mental health; but there are a lot of different layers between the Senior Leaders and the troop on the line.

The Soldier Readiness Processing Center on Fort Carson has a long hallway of chairs waiting to see the provider at the end of the day. At Fort Polk, it’s a waiting room that’s more like a circle, and the line to see the folks at the end of the day snakes back and forth, round and round. I imagine that there are variations on this theme at every military installation in America; after getting your eyes checked, your hearing checked, your blood drawn, and every other conceivable area of health monitored, a service member waits in this line for hours in order to see the provider for ten or fifteen minutes, if that.

When you go into the provider, they ask you the questions: “Having nightmares? Trouble at home? Suicidal thoughts?” Nope, Nope, and Nope. Everything’s cool. No issues here…while the entire time, combat is still ringing in their ears, and the voice inside their head is screaming, “just let me get the @#*$ out of hear so I can get drunk.” Is it every veteran, every time? No, of course not. Many times, things ARE going well. But it is extremely difficult to determine which are truly well, and which are just trying to appear well.

Why is that? Take a look at what happens in that two hour long line while waiting to see the provider for ten minutes. I’m sitting next to my buddy, who I just deployed with for nine to fifteen months. This guy or gal sitting next to me knows me in an intimate way that only someone who has shared combat can know someone. They probably know my favorite MRE, what type of music I listen to, what pisses me off, and what calms me down. They are my brother or sister. I trust them. Or maybe I’m sitting next to my squad leader, who I look up to, and who saved my @#$ a couple of times. They are the closest thing to Audie Murphy that I’ll ever know, and I’m pretty sure they could take ol’ Audie in a fight any day.

Do you know what that buddy or that Squad Leader is saying? “Better not say nothin’.” The ten minutes that we have with a provider we hardly know will never counteract two hours with someone that we trust our lives to. That’s the power of the individual stigma; the Department of Defense can say all day that it’s okay to seek mental health treatment, but if the idea does not get down to the individual squad and team level, then true change won’t happen.

I have a pretty recognizable Jeep Wrangler. Those who know me know what it looks like…and it is likely that, if I were still in the Army, that it would be more acceptable to some of my Soldiers if they saw my Jeep parked in front of a strip club or a bar than it would be to be seen parked in front of the mental health clinic. Is that the way it should be? Absolutely not! But I’m a big fan of reality…and that’s the way it is.

So how does that translate now that we’re out, or transitioning out? You can take the vet out of the military, but you can’t take the military out of the vet. Those core beliefs that we developed while we were in continue with us, become part of who we are. There are thousands of Veteran Service Organizations that will provide case management, help with housing, help with employment, time to take a break from the stress…but how many actually connect the veteran with the mental health services they need? Is the stigma of “crazy combat vet”, perpetuated by John Rambo, the Deerhunter, and countless wild-eyed pictures in the news, still alive and well in your community? Is it still alive in you?

The only veteran that I can make sure stays straight is me. I can make sure I take care of myself, change my own opinion regarding veteran mental health, or I can choose perpetuate the stigma. I can join my voice to others who are trying to make a difference, but ultimately, I am responsible for my own voice. You are responsible for yours. The stigma against veteran mental health starts with, and ends with, each of us individually. If you do your part, trust in me that I’m going to do my part.

4 Comments

Mark Chittwood · December 2, 2016 at 5:15 am

I wish the VA culture might some day realize that Veterans prior to the recent wars are also wounded warriors. I am a Chaplain at the VA and I meet a lot of Vietnam Vets who are still bitter over the reception that never happened. I have felt that if there was ever an inclusion into the ranks of being considered a part of the wounded warriors of yesteryear it would go along way with these Vets. I joined just prior to the ending of the Vietnam war and I saw how my friends were treated during and after that war. I personally prefer the name Wounded Warrior better than Disabled Veteran. When I see the word Disabled Veteran it feels like the focus is more on the disability rather than any progress I have made since first getting help. I think of a car being disabled, not running. An elevator is disabled, not working. A phone system is disabled because of a problem. The fire alarm had to be disabled because it is broken. We lost our connection to the internet therefore it has been temporarily disabled. Wounded Warrior has become very successful and there are far more needy Veterans than myself. But as one who suffers from PTSD, I feel like people are more cautious around us once they know we have PTSD. It’s like they never want to upset you for fear of what might happen. I overheard a colleague in an office suite introducing a new employee to some other co-workers. I heard her tell them that we need to be mindful that Mark suffers from PTSD so we try not to upset him. We don’t want him going postal on us. (It was part of the reason I left working there.) I wish the Wounded Warrior foundation would realize that it sounds more honorable to be a Wounded Warrior as opposed to a Disabled Veteran. This might just be my own issues that I need to work through in regards to my own mental health. But when reading this article it reminded me of the stigma and judgments that are made for a lifetime, when it has to do with Mental Illness. A VA Psychiatrist told me he meets secretly with active duty medical doctors to help them with their PTSD. They know if they seek help from the military their careers are over. They have to live with the big lie that they have a mental illness that they cannot talk about openly. When in actuality, talking to someone is the best thing for all of us.

Duane France · December 2, 2016 at 5:18 am

Mark, thanks for the feedback and your thoughts. Your observations are correct, and the stories of “you gotta watch out for this guy (or gal)” are common. Your description of active duty professionals seeking mental health services outside the military system is also common. Regardless of how help is received, though, any help is better than no help at all. Thanks again for your comments.

Let's Talk About Veterans for a Minute | Veteran Mental Health · July 9, 2016 at 6:14 pm

[…] The Stigma of Veteran Mental Health. The GAO recently published a report that indicates that stigma against Veteran Mental Health still exists in the DoD, and it certainly exists after veterans transition out of the military. […]

Who's Paying for Veteran Mental Health? | Head Space and Timing · January 12, 2017 at 5:33 am

[…] make the task of accessing mental health services impossible for veterans. There is, of course, the stigma attached to seeking mental health services. There is also the need for counselors and therapists to be culturally competent, both because they […]

Comments are closed.