During a recent discussion with Dan Savage, LinkedIn’s Veterans Program Manager, he talked about how transition for veterans was a two-way street. Yes, certainly, it would be great if the hiring managers in our industry of choice were able to understand us better, but we also need to do the work to understand that industry, speak their language, and make it as easy as possible for them to hire us.

That got me to thinking: did I ever expect something before I earned it? Pretty sure I never said to the Black Hat in Airborne School, “Hey, Man, how about you just pin those wings on me now? Trust me, I’ll jump out of the plane when the time comes.” Or to the Jumpmasters at the 82nd Airborne Division Advanced Airborne School, “come on, just give me a pass.” Like a tale of two cities, though, I then remember how I was as a private.

Before I enlisted into the Active Duty Army in 1994, I had spent a year in the reserves, and had gotten promoted to E-3/PFC. I was as proud of that tiny rocker as any 19 year old could have been. Strange, though, the Army could have cared less about how I felt about my rank, because when I enlisted into the Active Army, it turned out that I didn’t have enough time in service to keep it. I arrived in Germany with a pair of mosquito wings and a battle buddy that was a whole lot smarter than I was.

My first squad leader picks us up at the inprocessing building. After giving us a run down of the unit we’re going to, and what we do, he says, “so do you have any questions?” My much smarter battle buddy, who just spent three weeks listening to me lament my lost rocker, wisely keeps his mouth shut and looks at me. I, not being as intelligent as that, say, “How long before I can get promoted?” My squad leader looks at me out of the corner of his eye, and says, “cocky !@#%#^, ain’t ya?”

Looking back on it now, he was absolutely correct. Here I was, going into a situation that I knew absolutely nothing about, hadn’t even learned where the latrines were, and I thought that I was in a position to demand something. Problem was, I was a slow learner.

Fast forward three years, I’m looking at my first reenlistment. My uncle was Airborne in Vietnam, and served with the 101st. I wanted nothing more than to follow in his footsteps. When it came time to negotiate my contract, I told the reenlistment NCO, “I won’t reenlist unless you can guarantee me Airborne School en route to Fort Campbell.” She looked at me and said, “cocky @#$%(#, ain’t ya?” She politely explained to me that what I was asking for were two separate reenlistment options, school of choice and station of choice. In grand Army style, she said I could have one or the other, never both. I told her, “well, I guess I won’t reenlist, then.” She said, “I guess you won’t” and went back to her paperwork.

With both of these scenarios, the problem was that I had an overinflated sense of my own worth and an underappreciated sense of what the needs were of both my squad leader and the reenlistment NCO. What I was expecting of them, and what they were willing and able to give me in return for what I gave them, were two entirely different things.

I had value to them, sure. My squad leader saw my potential, and after he took my cockiness down a few notches with some well-placed…counseling…he helped me realize that potential. The reenlistment NCO knew that I was bluffing even before I did, and was able to get me Airborne School en route to Fort Bragg, which I recognize as one of the most formative assignments of my career. Once I overcame my overinflated sense of importance and started paying attention to what I could do instead of what I thought I deserved, things got a whole heck of a lot easier.

I was talking to a veteran recently about how our experiences were with the units that replaced us in combat. In the Army, we call it a RIP, or Relief in Place. One unit replaces another unit in an operational area. The new unit shadows the old unit for a while, then the old unit shadows the new unit for a while. Throughout several of our deployments, he and I had good RIPs and we had bad RIPs. The good RIPs were a result of the new unit coming in, listening to what the old unit had to say, and getting to learn the operational environment. The bad RIPs happened when the new unit didn’t want to hear anything about the tactics that worked, the tactics that didn’t, and how to stay alive. The “I’ve got this” attitude from a new unit always made me a little sick to my stomach, and it was usually a recipe for failure.

When veterans transition out of the military, we need to balance our expectations with the value that we bring. We may not need to start over from scratch, but we certainly aren’t going to start at the top. Just as my more intelligent battle buddy did when we first arrived in Germany in 1994, we may need to simply observe for a while. We need to understand the operational environment before we can start to make demands. We have to understand the needs of the hiring managers, and show them how we can satisfy those needs, rather than expect them to hire us because we know the correct side of a Claymore. Veterans absolutely bring immense value to any organization, and I’ll argue till I’m blue in the face against anyone who says otherwise.

The sooner we realize that the transition is a two-way street, the sooner we can demonstrate that value.

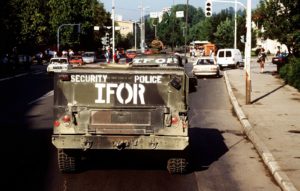

Postscript: Want to hear a funny story? While searching for an open-source photo to use to illustrate this post, I came across the picture above. It’s a photo of two HMMWVs driving through downtown Taszar Hungary, which was the main staging base for Task Force Eagle during Operation Joint Endeavor, the multinational peacekeeping force deployed to the former Yugoslavia in response to the Dayton Peace Accords. The photo was taken by a young (at the time) Air Force Staff Sergeant, Louis Briscese, a fellow veteran, and used with his permission. Unbeknownst to him, I was deployed to Bosnia at the same time as this picture was taken, and this was the deployment on which my dreams of becoming a Paratrooper were more important than my dreams of becoming a Screaming Eagle. Small world indeed.